Recently someone reached out to me on LinkedIN interested in Process Safety and Project Management, two topics which have defined the structure of my short career. Their background and context was outside of engineering, outside of process safety, and focused on Project Management fundamentals and how to incorporate safety reviews into project-based work.

Question: As a newcomer who is learning related fields, I would like to ask, when dealing with complex projects, what key safety management strategies do you pay most attention to?

Answer: I’m trying to make Process Safety my career – it’s all about knowing how to estimate risk using probabilities. AiCHE CCPS is a good resource for understanding all the elements that consist an OSHA PSM program, where Chemical Engineers typically fill positons. PSM regulated chemicals, sometimes referred to as the Highly Hazardous Chemicals list (in addition to analogues, similar compounds with similar hazards).

The easy stuff is identifying chemical hazards, high temperatures (>140F surface generally acceptable surface temp limit), rotating equipment hazards (rotary air lock pinch points, lathes).

The hard stuff is understanding the method of analysis which allows for a team of professionals (typically maintenance mgmt, operations/operators and mgmt, R&D “scale-up” chemists, process engineers, and a 3rd party safety consultant from a company like PSRG, BakerRisk, DEKRA or ioMosaic) to programmatically anticipate any failure modes of the system. The process is usually encapsulated in a “Process Hazard Analysis” committee which includes leading a 3rd party consultant through all the available Process Safety Information for a process, and breaking it into many smaller sections, called Nodes. Usually nodes are system boundaries drawn arbitrarily around certain vessels, or sets of vessels, in order to make the system easier to analyze and more digestible. The Process and Instrumentation Diagram (P&ID) should contain every PLC-connected sensor, every tank and vessel, every pump, every valve, and every pipe size and spec. The instruments and pumps have Tag # bespoke to the process, usually named following a traditional naming convention, or related to the process area numbering system that a site uses (I’ve never seen two alike, lol).

With the nodes selected, Excel is typically the backbone of a PHA.. let me share a simplified example from the internet (attachment). Imagine this as an excel file, with each possible failure mode highlighted, and its resulting consequence. Common ones include pump failures, motor failures, Instrumentation failures (point level sensor causing a tank to overfill). This is where redundant, independent technologies can be applied in order to better control a process and reduce the risk to a very high degree.

Typically I’ve seen most PHA leaders/adjudicators tend to ignore cases of Double Jeopardy, where two pieces of equipment must fail at the same time in order to cause the negative outcome.

Keep in mind from the project management side that this is all done during a CapEx project planning stages, sometimes called FEED (front-end engineering and design) or FEL-0 (front-end loading stage 0). Projects use a stage-gate concept, go/no-go decisions are made at each gate. For example, sometimes it takes a lot of money and engineering hours just to understand how much the later engineering and materials and construction will cost… so this would be an FEL-1 step, to gather budgetary quotes and start working on understanding solutions with contractors/vendors/engineers etc.

Anyway, the best strategy is to gather the best team of experienced professionals familiar with the exact operation in question. Operators are invaluable for their depth of knowledge on these topics, especially long-serving ones. They sometimes know that they are vital to the process but they’re also far and away the best practical knowledge source for how something really works and understanding how the basic things (accessibility for maintenance, ergonomics) can also be improved on a project to reduce . Someone with a lot of experience in a differnet process will tend to make assumptions and simplifications which may fail to highlight all potential failure modes of a system.

The typical PHA ends up producing a document that is several hundred pages of printed-out Excel, in which each node was thoroughly investigated. All the failure modes should be documented, and then modifications (if an existing system) should be tracked using an Action Item list, just as someone would do when following up on Management of Change procedures, or DHA (dust hazard analysis, same concept but for OSHA’s 2008 NEP on combustible dust safety alongside NFPA 660).

I think if you analyze my response there is a lot of overviews to gain depth of knowledge on – I could point you to a resource for that!

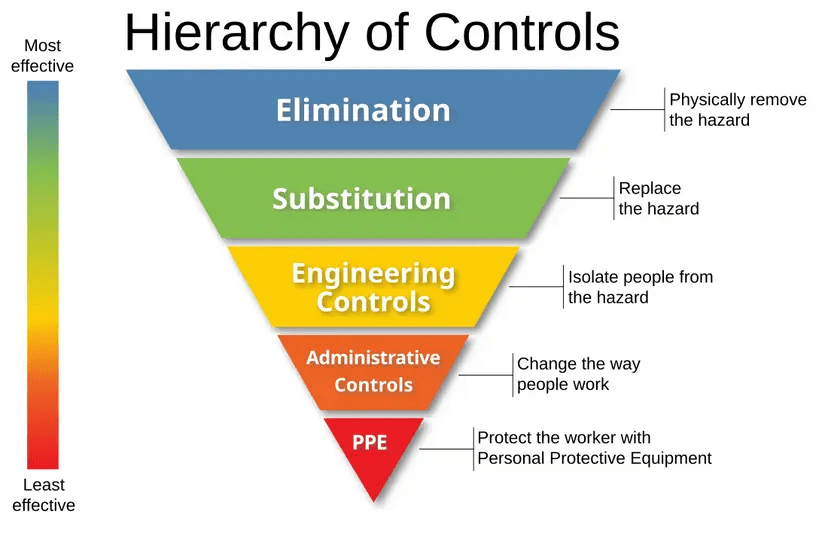

It matters in which context are you looking to apply safety management. My role is focused primarily on Process, that is separate from Environmental, Health and Safety, in that EHS is focused on the non-critical consequences (not immediately dangerous to life and health [IDLH]). Process safety has a bit more of the excitement of preventing catastrophe through thorough application of the Engineering Hierarchy of Controls concept.

Hope this highlights the field overall a little bit better. I have been involved as a participant with PHAs since I was a Project Engineer and I have since gone on to lead one. But if you had to skip everything else in safety in project concepts, you would not skip the PHA.

Lastly, there are analyses in Hazard Identification and Risk Analysis which also occurs early on in a project life-cycle. HazID and RA can take many forms, but usually start with identifying the material properties (from a manufacturer-mandated SDS for that particular product or CAS #) of any and all hazardous materials involved in the process.

All the best,

Devin